Africa Philosophy

What is Philosophy?

Philosophy refers to the understanding, attitude of mind, logic and perception behind the manner in which people think, act or speak in different situations of life. Mbiti, 1969, p. 2

If theories are like century-old roots of trees, then philosophy is the ageless soil on which those roots are nourished, moistened and supported. ASWDNet, 2021

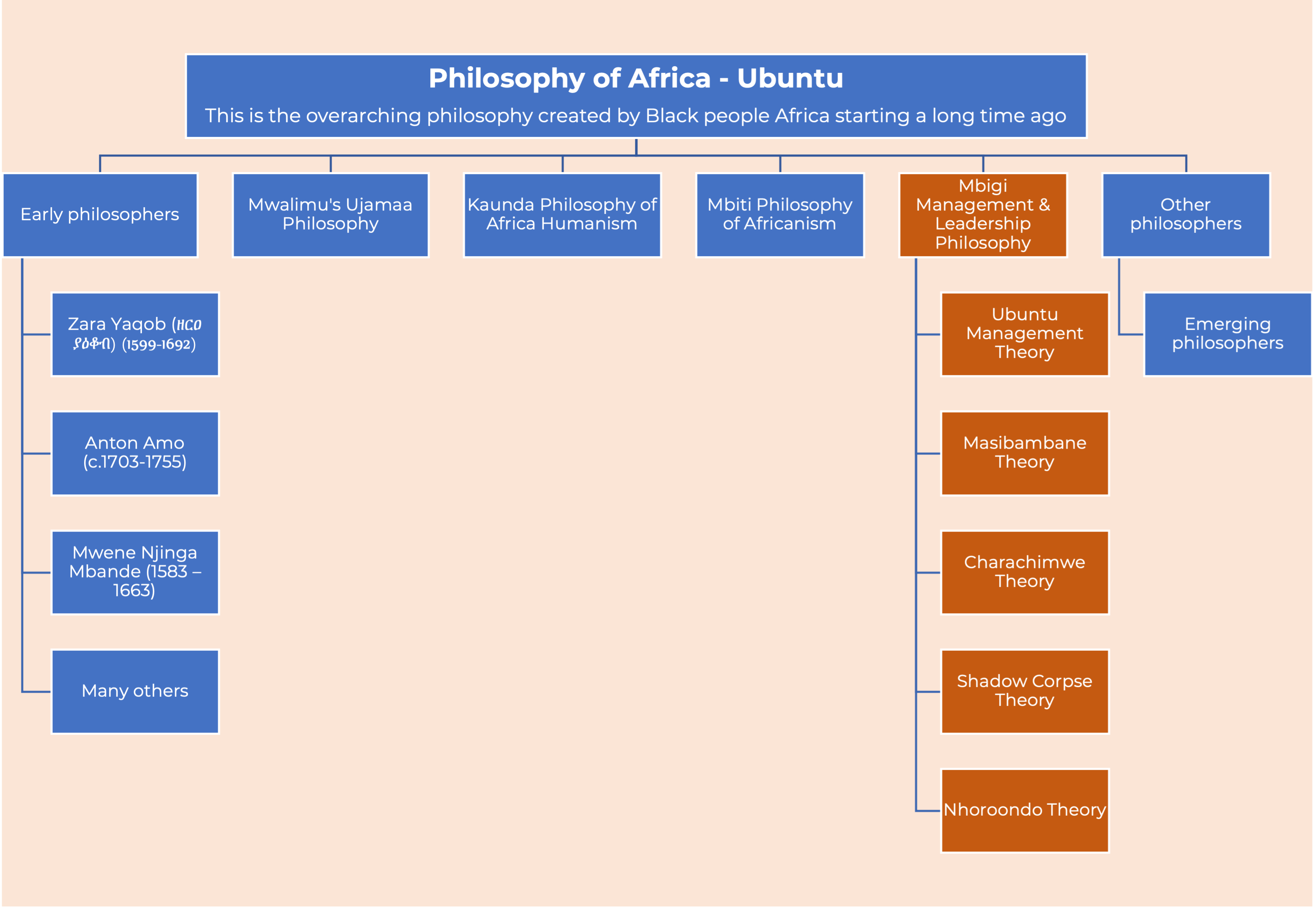

A philosophy contains a society’s deep thoughts and ways of looking at life. It shapes how people think about the family, community, society, environment and spirituality. It shapes how people think about reality, existence, reason, knowledge, religion, truth, race, values, mind, behaviour, justice and language. In the chain of knowledge, a philosophy sits above theories. Theories are derived from philosophy. A society usually has one philosophy. Basically, each continent has its one overarching philosophy.

What is Africa Philosophy?

Africa’s overarching philosophy is called Ubuntu. Ubuntu belongs to all who inherited it, and it can not be attributed to one individual author, one community or one country. ASWDNet, 2021

Summary of Africa Philosophy

Africa’s philosophy, can be summarised as follows:

We are Black people and Africa is the land we inherited from our ancestors (Nzinga, 1663; Nehanda, 1888; Asentewa, 1921; Diop, 1974). We value buntu (humanity), without it, people are not bantu (humans) but animals (Kaunda, 1966; Ramose, 2003; Wiredu, 1980). Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu, a person becomes human through others (Mbiti, 1969). Ndiri nekuti tiri, I am because we are (Samkange, 1981). We have our stories of creation, deaths, spirituality, religion and the environment (Mbiti, 1966; Nabudere, 2003). We value our different levels of family as sources of life, humanity and spirituality (Mbiti, 1969). We do have our own understanding of human relationships, we believe in umoja (collectivity) and ujamaa (communality) (Nyerere, 1968), ukama and ujamaa (relations and familyhood), reciprocity (usawa), respect and compensatory and restorative justice (Samkange, 1981). We value our environment, including the land, oceans and air we inherited from our ancestors and which we must use, protect and pass on to our offspring (Nehanda, 1888; Asentewa, 1921; Nkrumah, 1965). Each community must have enough land for each family to put up their home, keep their livestock, farm and call their own, and this includes all future generations. We can not achieve our humanity when others have not (Kaunda, 1966; Nyerere, 1968).

Ubuntu philosophy summary

Key aspects of African philosophy

Africa’s philosophy, written or not, covers these 5 aspects:

- Family

- Community

- Society

- Environment

- Spirituality

Therefore, we can say the important levels of aspects of Africa philosophy are the families, communities, societies, environments and spirits.

Important knowledge about African philosophy

- Basically, African philosophy belongs to the community, there are usually no individual philosophers. The individual philosophers have only expanded community ideas.

- Ubuntu philosophy is largely not written, it exist in different non-written formats.

- Some philosophers who have translated ubuntu philosophy to written literature, and these include:

- John Samuel Mbiti (1931-2019) – Africanism (ubuntu) and the Philosophy of African Religion

- Kenneth Buchizya Kaunda (1921-2021) – African Humanism (Ubuntu)

- Lovemore Mbigi – Ubuntu management philosophy

- Colonialism resulted in African philosophy and philosophers being overridden by western philosophies.

- More often than not, African writers, lecturers, teachers, researchers, librarians, reviewers and students know western or eastern philosophies than their own philosophies. This is a legacy of colonialism.

Philosophy shapes how we think about social work, how we define social problems and the interventions that we put in place. ASWDNet, 2021

Whose fault is it if no one knows about the philosophy of your grandfather and mine? Is it not your fault and mine? We are the intellectuals of (Africa). It is our business to distill this philosophy and set it out for the world to see. Samkange, 1980

African Philosophers

EARLY AFRICAN PHILOSOPHERS

Early philosophers

- Zara Yaqob (ዘርዐ ያዕቆብ) (1599-1692) was an Ethiopian teacher and philosopher born in Aksum, Tigray Province, Ethiopian Empire. He created the first Hatata (book of inquiry or investigation) in about 1669, basically, writings of his philosophy. Zara wrote his philosophy well before most western philosophers but as usual African ideas have been neglected. Zara was succeeded by his student, Walda Heywat who wrote Hatata 2.

- On discrimination he said “”All men are equal in the presence of God; and all are intelligent since they are his creatures; he did not assign one people for life, another for death, one for mercy, another for judgment. Our reason teaches us that this sort of discrimination cannot exist.”

- On harmony he said:

- On creation he said: “If I say that my father and my mother created me, then I must search for the creator of my parents and of the parents of my parents until they arrive at the first who were not created as we [are] but who came into this world in some other way without being generated.”

- On ethics he proposed that if it advances humanity or harmony in the world, then it is ethical.

- On religion he said the truth comes from observation of the natural world and not from religion.

- On slavery he said “”what the Gospel says on this subject cannot come from God. Likewise, the Mohammedans said that it is right to go and buy a man as if he were an animal. But with our intelligence, we understand that this Mohammedan law cannot come from the creator of man who made us equal, like brothers, so that we call our creator our father.”

- On so called Holy Scriptures he said all religions claim theirs to be true, despite contradictions, but they can only be one truth. “My faith is right, and those who believe in another faith believe in falsehood, and are the enemies of God.’ … As my own faith appears true to me, so does another one find his own faith true; but truth is one”.

- On gender he criticized the law of Moses for excluding women because of menstruation, yet it is the basis of procreation and love. He said the law ‘impedes marriage and the entire life of a woman, and it spoils the law of mutual help, prevents the bringing up of children and destroys love’. He gave Christianity, Islam, Judaism and Hindu the same criticism.

- Married Hirut, a servant woman or maid and treated her as a peer for ‘husband and wife are equal in marriage’. He said Hirut ‘was not beautiful, but she was good-natured, intelligent and patient’. ‘Since she loved me so, I took the decision in my heart to please her as much as I could, and I do not think there is another marriage which is so full of love and blessed as ours.’

- Anton Amo (from about 1703-1755) who was an Akan from Axim, Guinea, now Ghana. He was enslaved and taken to Europe, German where he became a renowned philosopher.

- Enlightened perspective of reason, treating all humans alike.

- Challenged slavery in On the Right of Moors in Europe (1729).

ORATORY PHILOSOPHERS

- Mwene Njinga Mbande (1583 – 1663), sister and advisor of the Ngola (king) of Ambundu Kingdoms in present day Angola. She had military training. The Kingdom had two nations, Ndongo and Matamba. In 1624 his brother died, potentially due to poisoning orchestrated by the by the Portuguese who were fighting the Kingdom for slaves. She was Queen for 37 years, defending the Kingdom from European Portuguese and Dutch using her cultural, military, diplomatic and political skills. She defended her position as a mwene, queen or woman leader and appointed women to positions, including her sister successor. She fought many wars, won some and defeated in some, driven from her nation and at one point only had 200 soldiers. The European Christians baptised her, and changed her first name and surname to Dona Anna de Sousa hoping to neutralise her philosophy. The first name was taken from the Portuguese governor’s wife and the surname was of the governor. But due to her strategy, she crated alliances and moves that helped her regain power and have the kingdoms under her rule again. Today, she is remembered as the Mother of Angola, a protector and negotiator. She has a large statue in her owner and is largely in recognised for defending self-determination, independence and cultural identity of her people. Although she did not write her philosophy, she embodied it.

- Mbuya (Grandmother) Nehanda Nyakasikana (the Girl) (1862-1898) – led Shona people against colonists led by Cecil Rhodes. She together with 13 others hanged by the colonists with the help of Christian missionaries but said deconolisation will happen ‘mapfupa angu achamuka’ – meaning my people will liberate themselves, decolonisation will happen. She also said ‘tora gidi uzvitonga’ meaning Black people needed to take the gun to liberate themselves because no one was going to do it for them. She objected to political, economic and spiritual colonialism. Among those who tortured her was a Christian Priest, Richartz who forced many of them to convert to Christianity, to be baptised and to adopt English Christian names. Mbuya Nehanda refused religious colonialism which was accepted by many of the men that were executed with her.

- Yaa Asantewa (1840-1921), the Queen Mother and Gate Keeper of the Golden Stool (Sika Dwa Kofi) of Ejisu, Ghana. When the British defeated her brother who was King (Asantehene) and exiled him to Seychelles, she became leader. British Governor Frederick Mitchell Hodgson demanded to sit on the stool in 1900, and this was a demand the Queen could not accept. She said “if you the men of Ashanti will not go forward, then we will. We the women will. I shall call upon my fellow women. We will fight the white (British) men. We will fight till the last of us falls in the battlefields.” The Ashanti were defeated, and the Queen and others were exiled to Seychelles where she died 20 years later. The Golden Stool has not been restored and is a cherished symbol.

There is a gender dimension in the first three philosophers, they show us that women had an important place and had influence in African societies before colonisation.

KAUNDA’S PHILOSOPHY OF AFRICAN HUMANISM (UBUNTU)

Kenneth Buchizya Kaunda was born in 1924 in Zambia. Together with his compatriots led a struggle against African colonisation, and later became Zambia’s as its founding president from 1962 to 1991, 27 years. He died in in 2021. His philosophy of ubuntu was writern in the 60s but summarised in 2007. Kaunda (2007)’s eight basic principles of African humanism or ubuntu are:

- The human person at the centre, people centred – “…This MAN is not defined according to his color, nation, religion, creed, political leanings, material contribution or any matter…”

- The dignity of the human person – “Humanism teaches us to be considerate to our fellow men in all we say and do…”

- Non-exploitation – “Humanism abhors every form of exploitation of MAN by man.”

- Equal opportunities for all, non-discrimination – “Humanism seeks to create an egalitarian society–that is, society in which there is equal opportunity for self-development for all…”

- Hard work and self-reliance – “Humanism declares that a willingness to work hard is of prime importance without it nothing can be done anywhere…”

- Working together – “The National productivity drive must involve a communal approach to all development programs. This calls for a community and team spirit…”

- The extended family – “…under extended family system; no old person is thrown to the dogs or to the institutions like old people’s homes…”

- Loyalty and patriotism – “…It is only in dedication and loyalty can unity subsist.”

Kaunda wrote “Zambian humanism came from our own appreciation and understanding of our society. Zambian humanism believes in God the Supreme Being. It believes that loving God with all our soul, all our heart, and with all our mind and strength, will make us appreciate the human being created in God’s image. If we love our neighbour as we love ourselves, we will not exploit them but work together with them for the common good (p. iv).” His two basic personal principles were relating with the creator, God and relating with neighbours or each other.

Sources:

Kaunda, K. D. (2007). Zambian humanism, 40 years later. Sunday Post, October 28. 20-25.

Kaunda, K. (1974). Humanism in Zambia: A Guide to its implementation. Lusaka. p. 131.

Kaunda, K. D. (1973). The humanist outlook. Longman Group Ltd., UK. p. 139.

Kaunda, K. (1966) A Humanist in Africa. London: Longman Greens

MBITI’S PHILOSOPHY OF AFRICANISM

Professor John Samuel Mbiti was not a social worker but a philosopher, theologian, and pan-Africanist. He was born in Kitui, Kenya. He studied English, sociology and geography at University College of Makerere in Kampala, Uganda in 1953. He lectured religion and theology at Makerere University from 1964 to 1974. His main philosophical ideas are contained in a seminal book published in 1969 titled African Religions and Philosophy. This book contributes significantly to African philosophy and has several ideas that are relevant for social work including, but not limited to ubuntu, decolonisation, indigenisation, spirituality, religion, ethnicity, kinship, birth, child development, initiation, marriage, procreation, death, ethics, justice and identity. Mbiti was an ordained priest, who led renowned world christian organisations. His philosophy is Africanism with a sub-philosophy, The Philosophy of African Religion.

Africanism

This philosophy answers the question, What does it mean to be African? Mbiti (1969, p. 106) said “What happens to the individual happens to the whole group, and whatever happens to the whole group, community or country happens to the individual. People, country, environment and spirituality are intricately related. The individual can only say: ‘I am because we are; and since we are, therefore I am”.

One-Africa

Mbiti asserted that Black African people have one binding philosophy and that they are one people despite sub-cultural variations among them. Underlying affinities and commonalities.

The Philosophy of African Religion

Definition of religion: Religion can be discerned in terms of beliefs, ceremonies, rituals and religious officiants (Mbiti 1969, p. 1).

Mbiti is regarded as the father of modern African theology. His main idea is Africa has its own religion. He challenged the European view that Africa has no religion of its own, and the colonial and Christian view that African religious views are primitive, demonic and evil, and Africans are savages. He argued that African religion and religious views are just as legitimate and require respect as Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Buddhism. He translated the New Testament from Greek into his mother tongue, Kamba. During the translation, he noted more than 1000 mistakes and misrepresentations that were in the westernised Kamba Bible. Promoted inclusion of African religions and philosophy within curriculum despite scepticism and opposition mainly from missionaries.

Mbiti said “Even though attempts are made to give Christianity an African character, its Western form is in many ways foreign to African peoples. This foreignness is a drawback because it means that Christianity is kept on the surface and is not free to deepen its influence in all areas of African life and problems.”

“Because (African) religion permeate all departments of life, there is no formal distinction between the sacred and secular, between the religious and non-religious, between the spiritual and material areas of life. Wherever the African is, there is his religion: he carries it to the fields where he is sowing seeds or harvesting a new crop,; he takes it with him to the beer party or to attend a funeral ceremony; and if he is educated, he takes religion with him to the examination room at school or in the university; if he is a politician, he takes it to the house of parliament Although many African languages do not have a word for religion as such, it nevertheless accompanies the individual from long before his death to long after his physical death. Through modern change these religions cannot remain intact, but they are by no means extinct. In times of crisis, they often come to the surface, or people revert to them in secret (1969, p2-3)”.

Community is at the centre of African life

African religion is not primarily for the individual, but for the community of which he is part. Chapters of African religions are written everywhere in the life of the community, and in African society there are no irreligious people. To be human is to belong to the whole community, and participating in the beliefs, ceremonies, rituals, and festivals of that community. A person cannot detach himself from the religion of his people, for to do so is to be severed from his roots, his foundation, his context of security, his kinships and the entire group of those who make him aware of his own existence. To be without one of these corporate elements of life is to be out of the whole picture. Therefore, to be without religion amounts to a self-excommunication from the entire life of society, and Africa peoples do not know how to exist without religion (1969, p2)”.

African religion can not be replaced, it is irreplaceable

“One of the sources of severe strain for Africans exposed to modern change is the increasing process (through education, urbanization and industrialisation) by which individuals become detached from their environment. This leaves them in a vacuum devoid of a solid religious foundation. They are torn between the life of their forefathers which, whatever else might be said about it, has historical roots and firm traditions, and the life of our technological age which, as yet, for many Africans has no concrete form or depth (1969, p2)”.

Shortcomings of borrowed religions

“In these circumstances, Christianity and Islam do not seem to remove the sense of frustration and uprootedness. It is not enough to learn and embrace a faith which is active once a week, either on Sunday or Friday, while the rest of the week is virtually empty. It is not enough to embrace a faith which is confined to a church building or mosque, which is locked up six days and opened only once or twice a week. Unless Christianity and Islam fully occupy the whole person as much as, if not more than, African religions do, most converts to these faiths will continue to revert to their old beliefs and practices for perhaps six days a week, and certainly in times of emergency and crisis. The whole environment and the whole time must be occupied by religious meaning, so that at any moment and in any place, a person feels secure enough to act in a meaningful and religious consciousness. Since African religion occupy the whole person and the whole of his life, conversion to new religions like Christianity and Islam must embrace his language, thought patterns, fears, social relationships, attitudes and philosophical disposition, if that conversion is to make a lasting impact upon the individual and his community (1969, p3)”.

Importance of orature in religion

“In African religion there are no creeds to be recited; instead, the creeds are written in the heart of the individual, and each one is himself a living creed of his own religion. Where the individual is, there is his religion, for he is a religious being. It is this that makes Africans so religious: religion is in their whole system of being (1969, p3)”.

One of the difficulties in studying African religions and philosophy is that there are no sacred scriptures. Religion in African societies is written not on paper but in people’s hearts, minds, oral history, rituals and religious personages the priests, rainmakers, officiating elders and even kings. Everybody is a religious carrier. Therefore, we have to study not only religious beliefs concerning God and the spirits, but also the religious journey of the individual from before birth to after physical death; and to study also the persons responsible for formal rituals and ceremonies(1969, p3-4)”.

Strength of Mbiti’s philosophy

- Mbiti’s work was decolonial.

- His work was based on field research in Africa with over 300 tribes

- Promoted orature, for example, proverbs, rituals, prayers and memories. Even though African philosophies were not written at the time, they existed in oral forms and practices. He collected and published over 300 African prayers

- His writing was based on his lectures at Makerere University in Uganda, making it relevant for Africa

- His seminal work was published in Africa, in Johannesburg

- He promoted indigenous languages.

- Challenged prejudice against the African cultural and religious heritage

Criticism and weaknesses

- More Christian focused and tried to Christianise African religious worldviews

- Okot p’Bitek, Uganda said Mbiti used western intellectual understanding of religion to interpret Africa’s view of God

- Married and settled in Switzerland, worked and died there, betraying his pan-Africanist ideology

MBIGI’S PHILOSOPHY OF UBUNTU MANAGEMENT

Professor Lovemore Mbigi is a social worker and motivational speaker whose work in South Africa has focused on ubuntu inspired management. He was born in Zimbabwe.

His major philosophical point is that Africa has its own management philosophy, and therefore African managers, governments and companies will not succeed by using foreign philosophies in Africa. This argument is really useful for social work, because most subjects on social work management use management philosophies from western countries yet we have our own philosophies. In social work training the works of Mitzberg, Taylor, Weber, McGregor, Maslow or Fayol is often seen in course outlines, despite being outdated, this work does not align with African values. This is what Mbigi challenged, his African dream in management. There are several elements or principles to his ubuntu management philosophy or theory, importance ones for social work are:

- Social and political innovation are more challenging but yet more useful than technical innovation. Managers need to balance social, political and technical innovation to succeed. An example of social innovation is using ubuntu in management, this is achieved by using the social experience of Africans in management. This experience includes oral literature (metaphors, proverbs, maxims etc), rituals, ceremonies, spirit, music and dance.

- Masibambane, which means ubuntu inspired business culture marketing, leadership, accountability, training and production. African organisations must be inspired by Africa’s own cultural heritage. African organisations can only compete in the global market by using a uniquely African management concept, embedded in the philosophy of Ubuntu (Mbigi, 1997).

- Western and eastern methods should not replace or override ubuntu, they need to be put in the context of ubuntu if they are useful. Imitation should be avoided.

- Cultural diversity should be valued in organisations.

- Collective leadership and decision making is important. Collective fingers theory (chara chimwe hachitswanyi inda) – Survival, Solidarity, Compassion, Respect and Dignity (Mbigi, 1997). All five fingers work together to achieve greater things.

- The role of managers is to facilitate the development of spirited and caring organisations. This is a source of motivation for workers.

- Shadow corpse theory – often, when organisations are not functioning, there is a ‘shadow’. This is an Africa metaphors, proverbs or maxim that says if a person dies and their shadow is seen, then there are unresolved issues. Mbigi says if an organisation is not doing well, there will be a shadow, and it will not go away until issues are resolved. This metaphor helps in diagnosing organisational problems.

- Nhorowondo – understand organisations, needs, motivations, processes and phenomena in their context. Family, community and culture are key considerations in Africa.

“Western genius in management lies in technical innovation. The Asian genius lies in process improvement. The African genius lies in people management”, (Mbigi, 2000).

“Although African cultures display awesome diversity, they also show remarkable similarities. Community is the cornerstone in African thought and life (Mbigi, 2005, p. 75).

Mbigi’s model is an important tool in decolonising management and make organisational processes more humane. It is also important to increase productivity in the social services, management of workers, development of organisations and engagement with people who use our services. It is time to teach African management philosophies.

Major works

Mbigi, L. (1997), The African Dream in Management. Randburg: Knowledge Resources.

Mbigi, L. (2000), In Search of the African Business Renaissance. Randburg: Knowledge Resources.

UJAMAA PHILOSOPHY

Ujamaa is the philosophy of Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere, former President of Tanzania. Nyerere was a great thinker, a philosopher considered to be way ahead of his peers in thought. His philosophy was pan-Africanist, nationalist and socialist. He is regarded as the father of ujamaa (familyhood) and maendeleo ya watu people-centred development. Philosophical principles are:

Maendeleo ya Kweli ni Maendeleo ya Watu

This means true development is people-centred. He said, “If real development is to take place, the people must be involved.”

Pan-Africanism

Nyerere’s pan-Africanism sought to restore the humanity and dignity of the African person. A United, prosperous and free Africa is what he preached. He supported liberation movements to reach this goal. He said “No nation has the right to make decisions for another nation; no people for another people.” He further said, “Unity will not make us rich, but it can make it difficult for Africa and the African peoples to be disregarded and humiliated.”

Ideological self-reliance

Nyerere believed is the use of ideas generated by Africans as opposed to ideas generated by other people – ideological self-reliance. Nyerere opposed state centredness, economic centredness, leadership centredness and donor centredness.

Ujamaa

Ujamaa was an original idea that Nyerere derived from utu (Ubuntu). Ujamaa means collectivity as opposed to individualism. The individual is part of the whole. He said “Ujamaa, then, or ‘familyhood’, describes our socialism. It is opposed to capitalism, which seeks to build a happy society on the basis of the exploitation of man by man; and it is equally opposed to doctrinaire socialism which seeks to build its happy society on a philosophy of inevitable conflict between man and man. We, in Africa, have no more need of being ‘converted’ to socialism than we have of being ‘taught’ democracy. Both are rooted in our past – in the traditional society which produced us. Modern African socialism can draw from its traditional heritage the recognition as ‘society’ as an extension of the basic family unit. But it can no longer confine the idea of the social family within the limits of the tribe, nor, indeed, of the nation. For no true African socialist can look at a line drawn on a map and say “The people on this side of that line are my brothers, but those who happen to live on the other side of it can have no claim on me”. Every individual on this continent is his brother.[…] But we should not stop there. Our recognition of the family to which we all belong must be extended yet further- beyond the tribe, the community, the nation, or even the continent- to embrace the whole society of mankind. This is the only logical conclusion for true socialism.”

Land ideology

Nyerere was vehement that land ownership was crucial and that everyone needed to own land instead of just a few people. This was opposite the colonial ideology that said Black people did not have land or should not own land and productive land.

African languages theory

Nyerere recognised that there was an alternative knowledge system that was embedded in the languages and cultures of the African peoples. To that end, he promoted Swahili as the language of commerce and government.

Political ideology

Nyerere believed that the world did not have one political system but that there were different political systems each with its strengths and weaknesses. “You don’t have to be a Communist to see that China has a lot to teach us in development. The fact that they have a different political system than ours has nothing to do with it.” “Capitalism is very dynamic. It is a fighting system. Each capitalist enterprise survives by successfully fighting other capitalist enterprises.” “We spoke and acted as if, given the opportunity for self-government, we would quickly create utopias. Instead injustice, even tyranny, is rampant.”

He attacked African politics “Capitalism means that the masses will work, and a few people, who may not labor at all, will benefit from that work. The few will sit down to a banquet, and the masses will eat whatever is left over.”

Education philosophy

Education must be useful to society. We do not get educated to be richer than others, but to improve society. “…intellectuals have a special contribution to make to the development of our nation, and to Africa. And I am asking that their knowledge, and the greater understanding that they should possess, should be used for the benefit of the society of which we are all members.”

Shortcomings

Nyerere’s vision of making Swahili the language of Africa lives on, and today Swahili is one of the official languages of the African Union. His work supporting liberation movements resulted in freedom in several African countries. He was also not tainted by corruption. However, Nyerere’s philosophy has some criticism based on part of his life and his achievements as President. While his policies were good, implementation did not go well, and his socialist ideas did not bear much fruit for Tanzania. It can be said that he was a leader at a much difficult period (1) he supported liberation of Africa that was opposed by the western world (2) the cold war impacted development and politics during his time. As a leader, he became more centred on his policies than his co-leaders.

Contributions

Nyerere, J. K. (1968). Ujamaa: the basis of socialism. In: Ujamaa : Essays on Socialism. Dar Es Salaam.

Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) (1967). The Arusha Declaration and TANU’s policy on socialism and self-reliance. Dar Es Salaam ; Dodoma: Publicity Section, Tanu, 1967.

OTHER PHILOSOPHERS

Gbadegesin, S. (1991). African philosophy: Traditional Yoruba philosophy and contemporary African realities. New York: Peter Lang.

Gyekye, K 1992. Person and Community in African Thought. In: Wiredu, K & K Gyekye (eds): Person and Community: Ghanaian Philosophical Studies 1.

Washington DC: The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy.

Gyekye. K 1995. An Essay on African Philosophical Thought. The Akan Conceptual Scheme. Philadelphia: Tempel University Press.

Gyekye. K 1997. Tradition and Modernity: Philosophical Reflections on the African

Experience. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kwame. S (ed) 1995. Readings in African Philosophy: An Akan Collection. New

York: University Press of America.

Masolo, DA 1994. African Philosophy in Search of Identity. Bloomington &

Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Menkiti, IA 1984. Person and Community in African Traditional Thought. In:

Wright, RA (ed): African Philosophy: An Introduction. Lanham. Md: University

Press of America.

Nabudere, D. W. (2005). Ubuntu philosophy: memory and reconciliation. Document. Kigali, Centre for Basic Research AND Nabudere, D. W. (2005). Afrikology, Philosophy and Wholeness. an Epistemology. Oxford, African Books Collective.

Nkrumah, K 1964. Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for Decolonization and

Development with Particular Reference to the African Revolution. London:

Heinemann.

Okolo, CB 1995. The African Person: A Cultural Definition. In Coetzee. PH & MES

van den Berg (eds): An Introduction to African Philosophy. Pretoria: Unisa Press.

Oladipo. 0 (ed) 1995. Conceptual Decolonization in African Philosophy. Four

Essays by Kwasi Wiredu. Ibadan: Hope Publications.

Senghor. LS 1964. On African Socialism. Mercer Cook (trans). New York: Praeger.

Wiredu, K 1992-93. African Philosophical Tradition: A Case Study of the Akan. The Philosophical Forum XXIV,I-3: 35-62.

Wiredu, K 1995. Custom and Morality: A Comparative Analysis of some African and Western Conceptions of Morals. In Oladipo, 0 (ed): Conceptual Decolonization in African Philosophy. Four Essays by Kwasi Wiredu. Ibadan: Hope Publications.