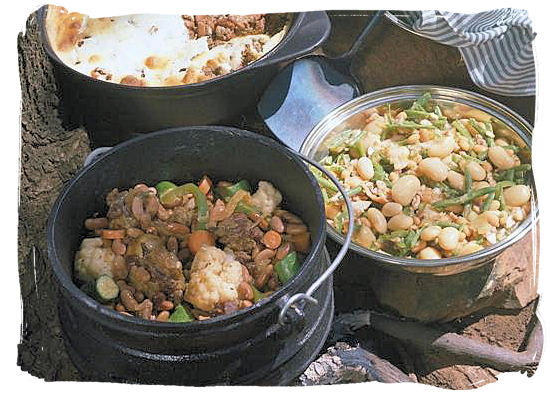

Food production in Africa, ideas for environmental and development work

This article is built on quotations gathered on this topic.

The numbers of people experiencing food security on the continent is astonishing.

“Across Africa, the number of people experiencing food insecurity at a moderate or severe level increased from 512 million in 2014 to 794.7 million people in 2021 – nearly 60% of the continent’s population. Troublingly, at this pace, Africa is not on track to meet the food security and nutrition targets of Sustainable Development Goal 2.” Paul Akiwumi, Director for Africa and Least Developed Countries, UNCTAD.

The most impacted countries are Nigeria, Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Somalia, and these countries import most of their food. In 2019, $43 billion was used to import food from outside Africa across the continent. This is despite that Africa has the most farmable land.

For African countries, most of which are net food importers, food security is largely dependent on global markets. At least 82% of Africa’s basic food imports come from outside the continent. In Eastern Africa, 84% of wheat demand is met by imports. Kilimo Kwanza.

But what are the roots of Africa’s food dependency?

Africa’s heavy reliance on food imports stems from several factors, including historical agricultural models, underinvestment in domestic food production, and underdeveloped infrastructure. Many African nations historically geared their agricultural sectors toward the export of cash crops—such as cocoa, coffee, and cotton—rather than producing food for domestic consumption. As a result, large portions of the continent’s food supply come from foreign sources, particularly staples like wheat, rice, and palm oil, which are essential for feeding rapidly growing populations (World Economic Forum).

If this issue is not addressed, vulnerable populations will continue to suffer and fall deep into poverty.

Despite the extremely challenging global context, homegrown challenges exacerbate Africa’s food security crisis. Africa is not realizing its own potential to feed itself. In 2021, 52% of employed people in Sub-Saharan Africa were active in agriculture, and roughly 45% of the world’s area suitable for sustainable agriculture production expansion is located in Africa, but the lowest agriculture productivity per worker rates are found within the continent. With production processes unchanged for many decades, most of African agriculture is still characterized by the farming of cash crops for export. For example, 14.8% of Côte d’Ivoire’s land is used for cocoa production. While the world is reliant on Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa, which makes up 40% of global supply, the country reaps few benefits. The labour-intensive agriculture leads to minimal investment, and most of the 5 million people, approximately 20% of the population, who depend on cocoa farming for their livelihoods remain in chronic poverty. As Côte d’Ivoire dropped the farmgate price of cocoa by 17.5% last year, the disparity caused by rising food prices will intensify food insecurity across the nation (Akiwumi).

Another compounding challenge is land tenure.

Another concern is that huge swathes of land are subject to long-term leases by foreign nations and private companies for the extraction of resources and the production of agricultural goods for export. While the scale of these land deals is unknown and reports vary, there is evidence for alarm. Large-scale land deals in Africa totalled 22 million hectares from 2005 to 2017 and are likely rising. The Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) is Africa’s policy framework for agricultural transformation. Created in Maputo, Mozambique in 2003, commitments to prioritize food security and nutrition, economic growth and prosperity in Africa were further strengthened in the 2014 Malabo Declaration (Akiwumi).

Commitments by the African Union and African governments is still in doubt, but there is hope.

The commitments were reinforced through the development of Africa’s common position on food systems, to help deliver on targets of the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and the Sustainable Development Goals. Despite featuring across Africa’s development agenda, and the African Union dubbing 2022 as the “Year of Nutrition”, the continent’s performance remains subdued. It was in Malabo that African countries adopted a resolution to commit at least 10% of their annual public budget to agriculture and rural development and to achieve agricultural value-added growth rates of at least 6% per annum. A cornerstone of this ambition was the implementation of national agriculture investment plans (NAIPs) – country specific visions and strategies to put the CAADP agenda into practice. At the same time, AU heads of state and government committed to ending hunger by 2025 and resolved to halve the current levels of post-harvest losses by the same year. In 2020, only four countries – Lesotho, Malawi, Ethiopia and Benin – had government expenditures in agriculture that met or exceeded the target of 10% of annual public expenditures. Africa-wide, just 2.1% of public budget expenditures were dedicated to agricultural spending. Similarly in 2020, only eight countries met the 6% agricultural value-added growth rate target – Lesotho, Zambia, South Africa, Senegal, Ghana, Angola, Kenya and Guinea (Akiwumi).

Implications for environmental and developmental work

The persistent food insecurity across Africa, despite its abundant arable land and a workforce dominated by agriculture, has critical implications for development practice. Training and education systems must shift focus from technical food security solutions reliant on global imports toward localised, decolonial models that foster food sovereignty. This means integrating political economy, historical agricultural policies, and land rights into development curricula.

In practice, development professionals must support policies that redirect agricultural investment toward domestic food systems, particularly staple crops, rather than export-oriented cash crops. Research must interrogate the political and structural roots of food dependency, including land tenure systems, state budgets, and international trade agreements. Evidence-based advocacy is needed to pressure governments to meet their CAADP commitments—especially the 10% budget allocation to agriculture. Development workers must also collaborate with local movements to challenge foreign land leases that undermine community resilience and food justice.

Environmental social work in Africa must respond to the deep link between environmental resources and food sovereignty. Communities’ declining access to arable land, water, and ecosystem services due to extractive land deals, climate change, and monoculture export farming has intensified food insecurity and poverty. Therefore, environmental social workers must advocate for equitable access to and control over land and environmental resources as a core social and ecological justice issue.

This includes supporting policies that return land to communities for sustainable food production, helping farmers transition to regenerative practices, and strengthening indigenous ecological knowledge systems. Practitioners must work at the intersection of land rights, climate adaptation, and economic justice to ensure that families, communities, and nations can generate their own food and livelihoods in dignified, sustainable ways. Protecting Africa’s remaining ‘farmable’ land from exploitative leases is essential to building local resilience and continental sovereignty.

Use the form below to subscibe to Owia Bulletin.

Discover more from Africa Social Work & Development Network | Mtandao waKazi zaJamii naMaendeleo waAfrika

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.