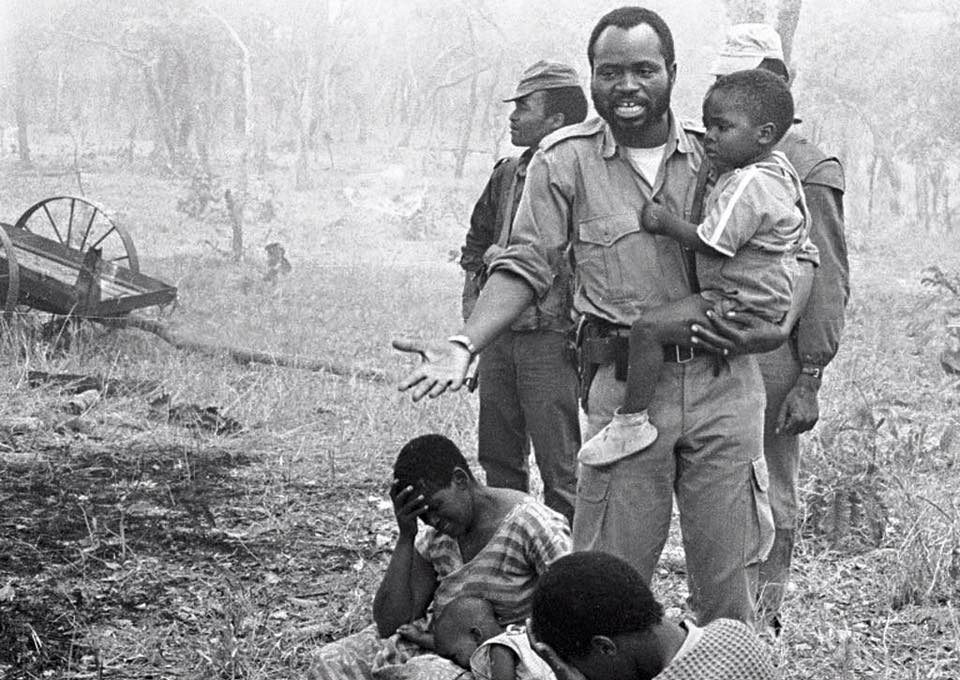

Samora Machel’s Theory of Superstition and its Firmer Implications for Social Work and Development

“To ensure our victory, we must destroy the remnants of colonialism in our minds. Superstition is one of its weapons — and we must defeat it.” — Samora Machel, 1975.

While growing up, and as an adult and leader, Machel experienced superstition. For him it was not a theory but an experience. He argued that superstition is a major obstacle to true liberation.

Superstition in Africa has deep cultural, religious, spiritual, and economic roots. Culturally, many communities develop beliefs in witchcraft, magic, and unseen forces as ways to explain natural events and maintain social order. Religiously and spiritually, both African religion and Abrahamic religion (Christianity, Islam, and Judaism) have beliefs in spirits, divine punishment, miracles, and the power of unseen forces, blending fear and reverence into everyday practices. Economically, superstition feeds on competition and scarcity: accusations of witchcraft or evil-doing are often used to eliminate rivals, claim land, or settle disputes, particularly in environments where resources are limited. Together, these roots create systems of belief that shape personal behaviour, community relationships, and responses to misfortune, making superstition a deeply entrenched part of many African societies.

Samora Machel defines superstition as belief in witchcraft, magic, prophecy, evil accusations, harmful spiritual healing, ritual sacrifices, blind fear of natural disasters, ritual sacrifices to control events, and any form of mysticism that undermined human action.

A deeper meaning of a luta continua

When Samora Machel, the revolutionary leader of Mozambique, said a luta continua — meaning the struggle continues — against superstition, he was making a powerful point with a deeper meaning. Machel compared colonialism with superstition, seeing both as systems that enslaved the mind and prevented real freedom. In short, he treated superstition as another form of colonial domination that had to be defeated for true liberation to happen.

In Machel’s view, independence was not complete just because the colonial armies had left. A deeper battle remained: the battle to free people’s minds from fear, ignorance, and manipulation. Superstition had, for centuries, been used by colonisers and local elites alike to maintain control over communities. Without challenging these deep-rooted beliefs, Mozambique and other African nations would remain trapped in a different kind of bondage.

Superstition as a tool of division and fear

The struggle was not simply against cultural practices, but against the ways in which certain beliefs weakened communities. Machel observed that when people believed their misfortunes were caused by witches, evil spells, or angry spirits, they turned against one another rather than working together. Witchcraft accusations often targeted vulnerable individuals — widows or the elderly — leading to violence, exclusion, and even death.

There is no positive superstition. Both African religion and Abrahamic religion (Christianity, Islam, and Judaism) reinforce belief in spirits, divine punishment, miracles, and the power of unseen forces, blending fear and reverence into everyday practices.

In Tanzania, superstition leads to the killing of elderly women accused of being witches, and people with albinism whose body parts are believed to bring wealth. In Ghana and Nigeria, there have been cases where children are branded as witches and abandoned by their families. In Madagascar, in some communities, the killing of twins is still practiced unless the parents run away with them forever.Belief in magic is manipulated by local leaders or opportunists who use fear to strengthen their own power. Across much of Africa, prophecy and spiritual healing are mixed into this system: people pay money to so-called prophets and healers who promise to remove curses or predict fortunes, often leaving communities poorer and more fearful.

Surprisingly, four decades after Machel’s death, a lot of people in Africa expect welfare, wealth and development to come superstitiously through prayer to God and ancestors, honouring prophets and shrines or lucky.

Machel understood that these practices did not just harm individuals — they prevented collective progress by keeping people isolated, suspicious, and unwilling to trust one another.

Superstition breaks social relations, breaks the cycle of reciprocity and respect, it causes physical and psychological pain and harm, results in economic loss, breaks spiritual strengths, can disable and cause death. It destabilises and retards development for individuals, families, community and society.

Who are most affected? Older adults, women, children, disabled individuals, including those with albinism and those who are barren and people who are creative, innovative and resourceful.

What the struggle against superstition looked like

For Machel, a luta continua meant that after winning political independence, the real work of building a free, just, and united society had to begin. The struggle against superstition involved dismantling harmful beliefs and promoting knowledge, solidarity, and confidence in human ability.

The government launched dynamisation groups — teams of young activists — who moved through rural communities to teach scientific explanations for natural events. For example, when crops failed due to drought, people were taught about climate patterns, soil fertility, and farming techniques, not angered ancestors or witchcraft. When people fell sick, health workers explained germs, sanitation, and nutrition, offering vaccines and clean water initiatives rather than reliance on rituals or charms.

In other parts of Africa, similar efforts were made. Julius Nyerere in Tanzania linked education with liberation, promoting rational thinking through the ujamaa villages. In South Africa, during the anti-apartheid struggle, activists ran workshops that discussed how superstition and spiritual fear divide oppressed communities.

Rather than rejecting all local knowledge, governments encouraged blending valuable herbal practices with scientific medical approaches, so that communities could preserve their identity while also advancing public health.

Expanding the vision of liberation

Samora Machel’s vision was not about attacking African culture, but about transforming it. He believed in the richness of African ways of life but wanted to clear away the parts that held people back from building a modern and fair society.

Thus, a luta continua was a call to keep fighting: against ignorance, against manipulation, against fear — whether it came from a colonial army or from within the community itself. In his view, political liberation without mental and cultural liberation was incomplete.

The work he started still echoes today in debates across Africa about how to honour the past while rejecting the forces that disempower people.

Machel’s theory of superstition in summary

Samora Machel saw superstition as a major obstacle to true liberation. In his view, superstition — including belief in witchcraft, magic, prophecy, evil accusations, harmful spiritual healing, ritual sacrifices, fear of natural disasters, and mysticism — was not just a cultural issue but a political and economic one. He believed superstition had been used historically, both by colonial powers and by local elites, to keep African people fearful, divided, passive, and easily controlled. Machel argued that even after achieving political independence, African societies would remain mentally and socially colonised if superstition continued to dominate thinking and behaviour. Superstition, for him, prevented unity, scientific understanding, trust, and collective development. It encouraged scapegoating, violence against vulnerable people, and the manipulation of communities through fear. Therefore, Machel made superstition a central target of the ongoing struggle — a luta continua — linking the fight for mental liberation with the broader project of building a modern, just, and free society. Education, health campaigns, and rational explanations for natural events were vital tools in this deeper, second phase of decolonisation.

Implications for social workers and development workers

For social workers and development workers, Machel’s struggle against superstition carries important lessons. Interventions in African communities must recognise that liberation is not only political or economic, but also mental and cultural. Efforts to promote health, education, human rights, and social welfare must address fear-based beliefs and practices that can harm individuals and fragment communities.

At the same time, workers must approach communities with sensitivity and respect, valuing local knowledge while firmly challenging beliefs and actions that cause exclusion, violence, or suffering. Development is not simply about providing services; it is about supporting communities to build confidence in reason, solidarity, and collective action — the very ideals at the heart of a luta continua.

Use the form below to subscibe to Owia Bulletin.

Discover more from Africa Social Work & Development Network | Mtandao waKazi zaJamii naMaendeleo waAfrika

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.